In this GOES-16 geocolor satellite image taken Thursday, the eye of Hurricane Irma (left) is just north of the island of Hispaniola, with Hurricane Jose (right) in the Atlantic Ocean.

NOAA/AP

Hurricane Irma is hovering somewhere between being the most- and second-most powerful hurricane recorded in the Atlantic. It follows Harvey, which dumped trillions of gallons of water on South Texas. And now, Hurricane Jose is falling into step behind Irma, and gathering strength.

Is this what climate change scientists predicted?

In a word, yes. Climate scientists such as Michael Mann at Penn State says, “The science is now fairly clear that climate change will make stronger storms stronger.” Or wetter.

Scientists are quick to point out that Harvey and Irma would have been big storms before the atmosphere and oceans started warming dramatically about 75 years ago. But now storms are apt to grow bigger. That’s because the oceans and atmosphere are, on average, warmer now than they used to be. And heat is the fuel that takes garden-variety storms and supercharges them.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted that the Atlantic hurricane season this year would be big. It said the most likely scenario would be five to nine hurricanes and three to five major hurricanes, which is above the long-term average.

Some of its reasoning is based on climate change. The eastern tropical Atlantic Ocean is the fuel tank of hurricanes, if you will, and big parts of the sea surface have been between 0.5 and 1 degree Celsius warmer than average this summer. Now, the Atlantic goes through normal cycles of warming and cooling that have nothing to do with climate change, such as in response to the El Nino and La Nina weather cycles. But this year neither cycle is active.

And whether or not Irma was emboldened by climate change, what’s more telling are hurricane trends. Big hurricanes in the Pacific as well as the Atlantic appear to be happening more often and are packing more punch than normal.

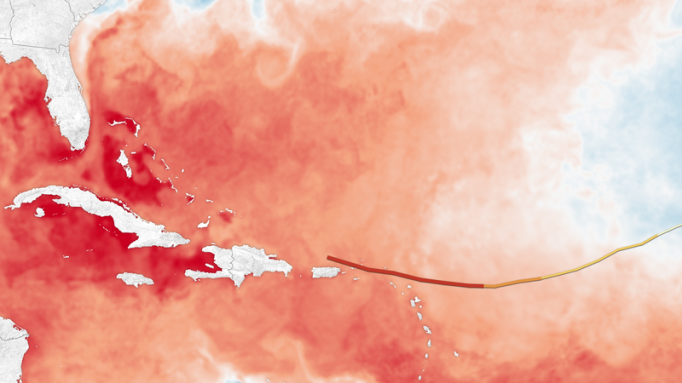

This composite image shows Hurricane Irma’s path as it moved into the warm waters of the western Atlantic. Sea surface temperatures are high this year.

NASA/NOAA

Climate scientist Kevin Trenberth from the National Center for Atmospheric Research explains: “Previous very active (hurricane) years were 2005 and 2010,” he says, and along with 2017, they experienced warm Atlantic Ocean temperatures. “So this sets the stage. So the overall trend is global warming from human activities.”

It’s worth noting that there are other things that made Irma big that have no clear association with climate change. Vertical wind shear in the hurricane “nursery” region of the Atlantic are weak this year. Strong wind shear at the right altitude can in essence “behead” a hurricane as it forms, so Irma has free rein to build. There’s also a long-term cycle in the Atlantic — the Atlantic Multi-Decadel Oscillation — that affects hurricane-forming conditions. Since 1995, the AMO is in the “on” position for good hurricane conditions, and in fact the period since then has been quite active for storms and hurricanes.

So, as with Harvey, these superstorms have always happened due to natural causes, but the underlying conditions in the oceans and atmosphere have primed the pump. You don’t need much effort now to turn a trickle into a gusher.